Et Sequitur Magazine, Issue 10

Issue 10 (Summer 2024)

The Words Beneath

By Michael Harris Cohen

“This is it,” Lily said.

It was just a smear of green on a lonely hill, an old cemetery in the middle of nowhere Bulgaria. Gravestones leaned like bad teeth, the names and dates long eroded.

It was our ninth graveyard in three months and I knew it wouldn’t be the last. Because the last one was supposed to be the last, and the one before that.

What had been a sort of gothic goof had turned weird obsession for Lily, or maybe it always had been weird? What did I really know about her? Either way, it had grown old for me.

All of it. Us.

Lily dropped her backpack to the ground. She didn’t bother with the pretense of taking photos, not anymore. Maybe that had been a lie—her whole Death Calendar thing. Who knows? She’d given up with the photos after the fifth graveyard.

She pushed her bangs out of her eyes and studied the tombstones. Her lean body bent at the waist. Her tallness had been firmly in the plus column when we’d first hooked up, six months ago. Now her gangly height seemed grotesque. Like a giant insect, she hopped from stone to stone, jerky-moving and too thin. Kind of like how she danced, a nervous grasshopper on drugs. I’d found it cute when we’d met in Portugal.

Funny how the things we like can become the things we hate.

I sat on the grass and pulled out my tobacco pouch. I rolled as I tried to remember who said, ‘familiarity breeds contempt.’ I smoked and mentally rehearsed my breakup speech for the umpteenth time.

I care about you, Lily. We’ve had fun. Loads of it. But I’m twenty-one and I don’t want to spend my summer touring the graveyards of Europe. I want to hang with the living not the dead. I think I might go back to school. I think I might . . .

Lily whooped and slapped a gravestone at the far end of the cemetery.

“I found it,” she said. “Grab the shovel.”

A year ago I’d dropped out of college and stuffed my life in a backpack. I’d been bored with everything. The Literature I read for class. The drugs I took and the parties I took them at. I’d wanted out of the states, out of my routine. My skin. I wanted to molt into something new.

But halfway through my Europe tour I’d become bored with travel too. One can only visit so many churches and museums, drink in so many hostels and bars, fuck so many strangers with accented and broken English, until it all starts tasting the same. Until it’s all bland as stale bread.

I’d met Lily at a beach rave in the Algarve. I’d taken too much MDMA and was slumped in the sand. Alone, a stranger in the crowd, teetering on the edge of a bad trip, when she’d approached.

She wore a mask made from bird feathers. Her eyes blazed through the plumy slits, green in the tiki-torchlight. Her voice was mellow as a breeze.

“You look lost, pretty lady,” she’d said, and though it was cheesy, I was lost, so I took her hand when she stretched it.

Her eyes crinkled into a smile behind her mask. She tapped her head. “I’ve got a compass in here. I’m an explorer.”

I remember laughing and liking her right off, because she laughed too, but at herself. Her stoned silliness.

“And what do you explore?” I asked, half-expecting some crude line about women’s panties, because I felt her vibing me with her eyes, and she still hadn’t let go of my hand. I was ready for yet another attractive woman who grew ugly when she opened her mouth and said something disappointing.

Instead, she stretched her long arms and swept in the whole scene. The costumed people dancing in the sand, the blooming moon, the thump of the techno bass. It was a perfect Instagram moment, the kind I’d fantasized when I’d left the states, but perfectly empty too.

And it was like she saw it through my eyes when she said, “A way out of all this shit.”

She’d bought a shovel yesterday. The man in the store hadn’t spoken a word of English but she’d mimed digging and he got the message. I’d made a joke about buried treasure and she’d shaken her head.

“Even better,” she’d said.

She was a good digger. She was already three feet down, into the grave. Sweat ran her face. I knew the taste of it, like olives, a briny taste that used to excite me. Though I’d started to dislike it, along with so many other things.

There’s a song about how the first six months of a relationship are heaven, then it turns to shit. That’s me.

The sun began to set. I smoked and wondered what the fuck I was doing here. Was I so numbed and sensation-starved that it was ok to sit by while my girlfriend, or whatever she was, digs up a grave? How had I become a person who hangs out in graveyards?

Our first together was in Prague, outside the city, a desolate spot on the edge of the woods. The castle’s spires rose in the distance, just above the tree line. I’d wanted to visit, to see the hovel where Kafka lived and wrote in the castle’s shadow. But Lily had other plans. She spent the morning poring over books. Crowley and Israel Regardie, magic texts I’d browsed as a teen but found boring and impenetrable.

“You’re into that stuff?” I asked Lily.

She’d smiled her winning grin. “It’s into me.”

At the graveyard, Lily set up her tripod and started taking photos. The sun was setting, the golden hour, and the light made the gravestones look dipped in honey.

Lily had told me about the Death Calendar our first day together, on the beach in Portugal, where we’d offset our hangovers with a pitcher of sangria.

“Every month will be a different graveyard from around the world. I’ve shot two dozen cemeteries already.”

Her pictures were stunning. The obelisk stones of Turkey, the above ground graves of New Orleans. She said the dates on the calendar would be famous death dates, rather than birthdates and holidays: Jim Morrison, Oscar Wilde, Anaïs Nin, so on. It seemed artsy and the kind of thing one might make money on. Who knew? As she’d joked, “Death never goes out of fashion.”

She wandered the graveyard in Prague, then suddenly bent to pick a flower. She held it up in the fading daylight, studying it as if she was a botanist. Then she tucked it into a pocket in her backpack.

After that, in the other cemeteries that followed—in Germany, in France, in Spain—she always took something after shooting her pictures. Another flower. A stone. A pinch of dirt. She’d collect them but never tell me why.

She’d grin and kiss me. “A little mystery makes love last.”

The dull clunk of metal on wood snapped me back. I could guess the sound. The sound of shovel meeting coffin.

I stood up as Lily worked the last scoops of dirt from around it. She was mumbling to herself, a thing she did when she was excited. Another thing I’d once found cute and eccentric that now bugged me.

Then she tossed the shovel aside and jumped in. A raspy scrape filled the air. She’d wrenched it open.

“Voila,” Lily said.

Last night we’d camped on a beach by the Black Sea and Lily showed me her notebook, haloed in the lantern light. It was a tattered thing, one of those Moleskin books with the elastic band. Inside were notes and symbols I couldn’t understand.

I rested my head on her chest, trying to read it. Her cursive was an EKG line. I wondered what it said about her personality. She flipped ahead. A neatly drawn map of Europe filled two pages. There were no names for the countries, but I knew them. Five we’d visited together. All connected by lines.

“What does it mean?”

Lily traced the intersecting lines with her finger. “Don’t you see it?”

I studied it, turning my cheek against the soft skin of her bare chest. “Nope.”

She kissed the top of my head and whispered in my ear. “A pentacle.”

Her finger landed at the tip of the star. It was the place we were at now, in Bulgaria. This spot by the sea, a few kilometers from a village whose name I couldn’t pronounce.

I sat up, head brushing the nylon of the tent. Lily still stared at the book. “What’s the point?” I said.

Then she told me about the Thracians, the people who’d populated this land centuries ago. The waves lapped the shore outside our tent. For a moment, as she talked, I had the feeling we were floating in the sea, that our tent was a raft adrift in the rolling dark.

In her notebook she’d written Orpheus. And underneath, Don’t look back.

I pointed to it.

“He was Thracian,” Lily said

“He’s a myth.”

Lily smiled. “Where do you think myths come from?”

“So what, you hope to find a golden harp?”

Lily laughed, then turned off her light. “Something better,” she’d whispered in the dark.

Surprise then relief: the coffin was empty except for a layer of dirt at the bottom. Small mushrooms sprouted in it. I winced as Lily plucked a handful’s worth, tucking them in her shirt pocket, then climbed out of the grave. She scooped the shrooms from her pocket and held them out to me.

“These are not your garden-variety cubensis.”

She popped two larger caps into her mouth and chewed. She made a face, like she’d bit into a clod of dirt, then smiled. “Not so bad. Meaty tasting.”

She plucked one and held it to my lips. “Just a taste.”

I shook my head. “No fucking way.”

But her fingers hung there, suspended in front of my mouth, a dentist with a difficult child.

“You can’t cross over without it,” she said. “Break on through, baby.”

I wasn’t prudish about drugs. I’d tried pretty much everything even before I’d met Lily. I’d smoked DMT and once snorted heroin with one of my modernism TA’s. And Lily was a good psychedelics partner, the best I’d ever had. We’d dropped mescaline for a reeling, color-drenched day at the Louvre, and done ketamine at Berghain. But eating a mushroom grown in a coffin, on God knows what or who, that was my line in the sand.

“I thought you were an explorer, too?” Lily said. She smiled.

“I’m tired of exploring. Let’s go back.”

“Just one.”

I sighed. She’d never give up. She was always pushing, pushing, pushing. I reached out my hand, then flipped her the bird.

She did that thing with her eyes, like she could make them twinkle at will. Like she’d done that night in Portugal, when she’d saved me from my bad trip. I sighed again, opened my palm, and she dropped a marble-sized cap on it.

I popped it in my mouth.

It tasted horrible, ancient and sour. I thought of mummies and nearly gagged.

She laughed and hugged me. Then she popped the rest of the mushrooms and, when she wasn’t looking, I spit mine out.

We sat and shared a cigarette and, almost immediately, the mushrooms seemed to hit her. I knew her tripping face. Her smile stretched elfish; her green eyes grew shinier. She was a giggler, usually, which had always made tripping with her a blast.

Our legs dangled over the empty coffin. “Who was buried here?” I said.

“It’s not about who. It’s about where. It’s a door.”

“A door? You’re wasted.”

“I am,” she said and giggled and so did I. Till suddenly she stopped.

Her smile fell and her face slackened. It felt like a wind had blown in and changed the weather, shifted her whole mood. Her eyes narrowed and focused, drawn back to the grave. I took her hand.

“Lily let’s go back We’ll get a bottle of wine. Trip on the beach.”

Instead, she yanked her hand away and hopped into the grave. On her knees she started scooping dirt from the coffin bottom and tossing it out. She was clearly losing it and whatever moment we’d just had, she’d killed it. Like she always did lately.

I hated how she got in the graveyards, and it seemed to get worst with each one we went to. With each item she had gathered.

“Shine your phone down here,” she said.

“I’m going,” I said. “This is too fucking much.”

“Just for a little. Then go if you want. I don’t give a shit.”

“Clearly,” I said as I flicked on my flashlight.

This would be it, I thought, stooping over the grave and shining the light down. This would be our final page. I’d do this for her and, when she came down, I’d tell her we were done and why. She was too out there, too freaky. And selfish. I’d had enough of travelling with her, enough exploring. I wanted stability. And I realized I wanted, I needed, home.

“Look,” Lily said.

She’d scooped away most of the dirt and the bottom of the casket was visible. It looked odd. Then I realized why.

It wasn’t a bottom. It was a door, though narrow and laid flat like a table. A small metal knob, tarnished green from time, stuck from one side.

Or it was the shroom I’d sucked? Because I did feel odd, a wobbly feeling, micro-trippy, drifted my gut. And that was just from holding it in my mouth for 20 seconds.

What was Lily feeling after wolfing a handful?

“See,” she said. “A door. “The door. Door. What a funny word. Doooooor.” Then she laughed but it didn’t make me feel any better, because the laugh was disturbing, high and whinnying, the chortle of a crazy person.

She pulled and pulled at the handle. Then she regripped with two hands and yanked with all her strength.

The door gave way with a shumpf and a creak of long-rusted hinges. I shined my phone into the dark beneath. Dust swirled and the smell was indescribable. Something that hadn’t been opened in a very long time, but it was somehow sweet, cloyingly so, not rotten.

Then I saw what lay beneath.

It wasn’t real. It couldn’t be. I must be tripping. I must be.

Because a narrow staircase, cut from stone, descended into darkness.

Our fascination with death was one of the things that had drawn us together.

We’d both had a parent die when we were young—her father, my mother—and we’d both made half-assed attempts at suicide as teenagers. Pills for me, a razor in the bathtub for Lily. We’d laughed at our teenage cluelessness, at how there was so much more life beyond our stupid towns, beyond being bullied in high school, and our tortuous family dynamics. We’d laughed at how our lives had seemed like a dead-end road at 16, while the whole world had been waiting, just around a corner we couldn’t see.

I stood at the lip of the grave. Her voice was strange and throaty when it came. “Let us go, you and I.”

I smiled at the Eliot quote and fed her the next line, “When the evening is spread out against the sky.”

But she didn’t bite, dropping our game. She turned away. Her gaze already walking those stairs. I knew there was no way she wasn’t going down, and I knew there was no fucking way I was.

“I’m going back. To the campsite.”

Her body swayed, as if a wind gusted from below.

“And when I go back, I’m packing up my shit and leaving. I’ve had it, Lily.”

Then she locked eyes with me, but it was like she didn’t know or see me. Like I was part of a world that no longer made sense.

Then she turned, started down, and disappeared.

I smoked and waited.

In the time of a cigarette, I went from irritated to pissed. How long was she going to stay down in this crypt, or tomb, or whatever it was? Did she think I’d follow her anywhere? Or was I just supposed to wait here? Or walk back through the woods to the beach, alone, in the dark?

Fuck her.

I marched a hundred meters down the hill, my phone lighting the way, before pissed off diluted to worry. Then came guilt. I cursed my impulsive nature. The same wild hair that had launched me across Europe with a near stranger, was the one that had broken up with her when she was tripping balls.

It wasn’t right. I should have at least waited till she’d come down. I didn’t have to do it then and there.

I stopped, cursed again, and started back up the hill.

When I got back to the grave there was no sign of her. She was still down there, curled up in that crypt, probably losing her shit, if she hadn’t lost it already.

Fuck. I had to get her.

I lowered myself down, holding onto a thick root as I balanced on the lip of the coffin. I shined my phone down. Dust motes whirled in the beam, spiraling down the staircase.

“Lily,” I said. Then again, louder.

And as I started down the staircase, the light filling the narrow passage, I wondered if Lily was having the worst trip of all time. And though I was super creeped out I had to go. I had to make things ok.

But after two minutes of descending, I started to wonder when I’d hit bottom, and where the hell Lily was.

How deep did this thing go?

I heard something below. I stopped. A distant shuffle, maybe shoes on the stone steps. Then a sound, like faint voices in the distance. Murmurs.

“Lily!”

Silence.

The utter strangeness of it all smacked me. How had they made these steps, these perfectly even cut stones that seemed to never end? Who’d made them?

How deep did it go?

I’d told myself I’d go another ten steps, then turn back. Maybe she wasn’t even down there. Maybe she’d come back up and went looking for me? But twenty minutes later I still trod downward, though it felt like nothing. Like barely a minute. I couldn’t believe it when I looked at my phone, checking the battery for the flashlight. 18% and dropping.

I had to turn around. Go back.

But I didn’t. I kept descending, even as a terrible feeling came over me, that I couldn’t stop if I wanted, that something pulled at me, an invisible string. Though it didn’t hurt. It felt like falling asleep. Like sinking. Like the deeper I went the less the world above seemed to matter. Like the rope to the world above thinned and frayed as one from below grew stronger.

Then, at last, I saw Lily in the light beam. Stopped on the steps, her back to me. Waiting. Her long arms stretched to either side of the tunnel. I thought she was resting, trying to catch her breath.

But it wasn’t that.

Her muscles strained against the walls. She had to press against them to keep from being pulled down. I knew because I felt it too. I didn’t want to stop either, even though I’d finally found her.

The sound of voices was louder, drifting up from below, just beyond intelligible. Though I thought I could almost make out words, almost, or my mind was playing tricks.

I grabbed Lily’s arm.

“We have to go back,” I said. “Let’s go back. To the tent. The beach.”

She finally turned her head. I’d expected her expression to be one of fear, but she smiled wide. Her ecstatic tripping face.

Her eyes danced over my face. “I waited. It’s so hard to stop, but I waited for you. I want us to cross over together. I want to see what you become, what we become, when we cross over.”

“Lily. You’re high as fuck. We need to go back. Come on baby. Back to the beach. We’ll do a night swim. I’ll rub your feet. Then we’ll go to Athens, like you wanted.”

Her eyes settled into mine and I read her answer in them. There wouldn’t be any trips to Athens. No more raves in the Algarve. No museums on psychedelics. No night swims or sex on the beach. There was only one place left for her to go.

She smiled but there was something in her eyes, a tiny speck behind the stoned euphoria. A part of her that wanted to go back. To the living. A part that loved me more than all the exploring.

And there was something else in those beautiful, green eyes. A flicker of terror.

Then she dropped her arms and started down. I tried to grab her around the waist but she’s twice my size, and she pushed me away like I was made of twigs and string. I fell hard on the steps, cracking my phone, snuffing the light.

“Lily!” I screamed in the darkness

But the only response was the shuffle of her boots on the stone, fainter and fainter. I wrestled with which way to go, as I felt the thing pulling me down, like just the taste of that shroom had cranked up gravity. And I heard the voices, could now make out a word, almost, or thought I could, as murmur thrummed in my head.

Some feeling, a primal instinct for survival, whispered in my blood:

If you understand the words you can never return. Never. Never ever ever.

I shouted Lily’s name to drown out the voices. I shouted till I lost my own voice, holding on to the step as if I were hanging from a ledge.

Till there were no sounds left to make, nothing but the rasp of breath in my ragged throat.

I don’t know how long it took me to get back to the surface. Time stopped. I climbed in the dark, on hands and knees. I felt the pull the whole way, though it grew weaker as I grew closer to the top. I thought of everything I wanted to return to. The books I’d read and those I’d vowed to read. The taste of wine. The smell of the sea. The tang of fresh lemon. The sounds of piano and violin. I cried and crawled and wove my rope to the surface from a litany of the living.

When I finally emerged from the grave, exhausted and desperate for water, the moon was high and full. A silver plate that held nothing. Silent and indifferent to the hell I’d endured. Uncaring for Lily . . . my lost Lily.

I stumbled down the hill.

I guzzled water from a fountain in town, soaking my head, washing the dirt and dust from my skin. Though I couldn’t really wash it off. It was like something had seeped into me from below, a thick film I’d never wash off.

The next day I packed a few of my things, though I left most of our stuff on the beach. Numb, I picked up Lily’s notebook and stuffed it into my bag. I had no tears left.

I abandoned our sleeping bags, our tent. I thought about calling the police. But what would I say? What would they do?

On my flight back to the states I opened her notebook. There were poems she’d never shared with me, beautiful word-snapshots of things she’d seen or done. But mostly there were the indecipherable magic notes. And the map with the pentacle. And those block printed words

Don’t look back.

Then I got it. Like Orpheus. She knew. She knew she’d want to look back.

Don’t look back.

And I try not to, though I can’t help myself. Even after I put an ocean between us, and then an ocean of time, years, decades, I still think of Lily, forever descending those stairs. Her endless walk into the underworld. The words beneath her growing clearer

Sometimes I hear the voices from below. In dreams they come. I hear them more with each passing year.

Louder. Clearer.

One day, I am terribly certain, I’ll understand their every word.

This story was originally published in the Picnic in the Graveyard: An Anthology of Cemetery Horrors, edited by Brhel & Sullivan and reprinted in The Dark Magazine.

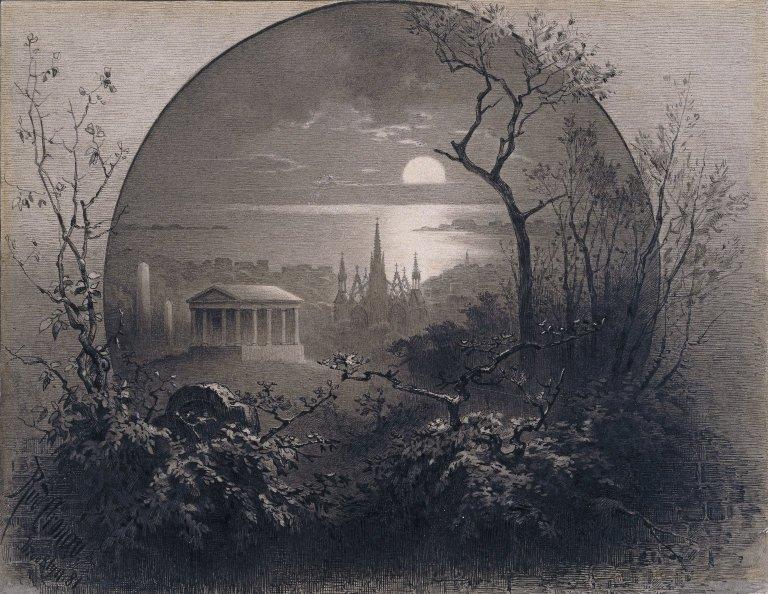

Cover art: View from Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn, circa 1881 by Rudolf Cronau

Share this story on Twitter

Michael Harris Cohen has published work in Conjunctions, On Spec, Pseudopod, and numerous anthologies. He is the winner of F(r)iction’s short story contest, judged by Mercedes Yardley, as well as the Modern Grimmoire Literary Prize. He’s received a Fulbright grant for literary translation and fellowships from The Djerassi Foundation, OMI International Arts Center, Hawthornden Castle, and the Künstlerdorf Schöppingen Foundation. His first book, The Eyes, was published by the once marvelous but now defunct Mixer Publishing. His latest collection, Effects Vary, is available from Cemetery Gates Media. He lives with his wife and daughters in Sofia, and teaches in the department of Literature and Theater at the American University in Bulgaria. Find him at MichaelHarrisCohen.net.

© Copyright Et Sequitur Magazine